You may view the SVG vector code for the Latin portico image at my Codepen account

Here is a Microsoft Word version of this blogpost:

Here is a pdf version of this blogpost:

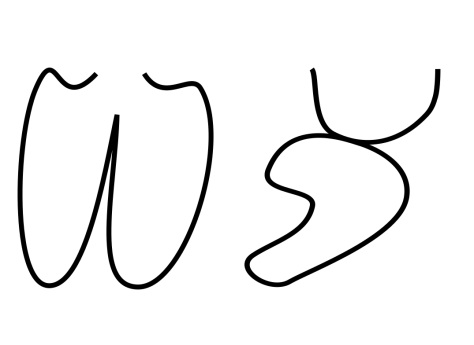

The Classical Latin Alphabet:[1]

Introduction:

In beginning our study of the Classical Latin language, we shall begin with its alphabet. We shall learn the Latin name of its letters, and how these letters ought to be pronounced.

The Latin word for ‘alphabet’ is ‘abecedārium.’[i]

Body:

Classical Latin possesses an alphabet that contains twenty-three letters. These letters are as follows:

| The Classical Latin Alphabet: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Lowercase Letter: | Latin Uppercase Letter: | Letter Name in Latin: | How to Pronounce the Letter’s Name in Phonemic Transcription: |

| a |

A |

ā |

/aː/ |

| b |

B |

bē |

/beː/ |

| c |

C |

cē |

/keː/ |

| d | D | dē | /deː/ |

| f | F | ef | /ɛf/ |

| g | G | gē | /geː/ |

| h | H | hā | /haː/ |

| i[ii] | I | ī | /iː/ |

| k | K | kā | /kaː/ |

| l | L | el | /ɛl/ |

| m | M | em | /ɛm/ |

| n | N | en | /ɛn/ |

| o | O | ō | /oː/ |

| p | P | pē | /peː/ |

| q | Q | qū | /kuː/ |

| r | R | er | /ɛr/ |

| s | S | es | /ɛs/ |

| t | T | tē | /teː/ |

| u[iii] | V | ū | /uː/ |

| x | X | ix | /ɪx/ /ix/ |

| y[iiii] | Y | ī Graeca | /iː ˈgra͡ɪ.ka/, /iː ˈgra͡ɪ.kɑ/ |

| z | Z | zēta | /ˈsdeː.ta/, /ˈzdeː.ta/, /ˈsdeː.tɑ/, /ˈzdeː.tɑ/ |

Conclusion:

In this chapter have examined the alphabet of the classical Latin language. We have committed the knowledge:

- that the Latin word for ‘alphabet’ is ‘abecedārium;’

- that the Latin Alphabet comprises twenty-three letters;

- which letters comprise the Latin Alphabet;

- the names of the Latin letters;

- how the names of the Latin Letters are pronounced in Latin.

to memory. Our now having acquired the above-listed knowledge, we can now move forth to following chapters that will treat of the pronunciation of Latin in greater detail.

Endnotes for the Chapter, ‘The Classical Latin Alphabet:’

[i] The Latin, ‘abecedārium,’ genitive singular: ‘abecedāriī,’ is a 2nd-declension neuter noun. The first four letters of the Latin alphabet are:

‘ā,’ ‘bē,’ ‘cē,’ ‘dē

.

Hence from the first four letters of the Latin alphabet we derive the word:

‘“ā,”-“bē,”-“cē,”-“d’”-“-ārium.”’

The 2nd-declension neuter nominal suffix: ‘-ārium,’ genitive singular: ‘-āriī,’ denotes ‘a place where things are kept.’ Where do we keep our letters? We keep our letters in an ‘alphabet,’ or, in Latin, in an ‘abecedārium.’

Hence, etymologically, in Latin, an ‘abecedārium,’ can be defined as: ‘a place where we keep the Latin letters, “ā,” “bē,” “cē,” “dē,” etc.’

[ii]Properly speaking, there is no ‘j’ or ‘J’ in Latin. However, one will often see this character’s being employed—usually in Church texts and other works composed later than the Classical epoch—to denote a consonantal ‘i,’ or ‘I.’ In Latin, ‘i,’ as a vowel, is pronounced, when short, as /ɪ/ or /i/; and when long as /iː/.

In Latin, consonantal ‘i’ can be represented by the IPA symbol, /j/. The consonantal ‘i,’—or ‘j,’ as one sometimes sees (in Church texts)—represents this very /j/ sound. The consonantal ‘i’ in the Latin word, ‘iugum,’ or ‘jugum,’ /ˈjʊ.ɡʊm/ that means ‘yoke,’ is pronounced as the ‘y’ in the English word, ‘yurt,’ i.e. as: /jεːt/.

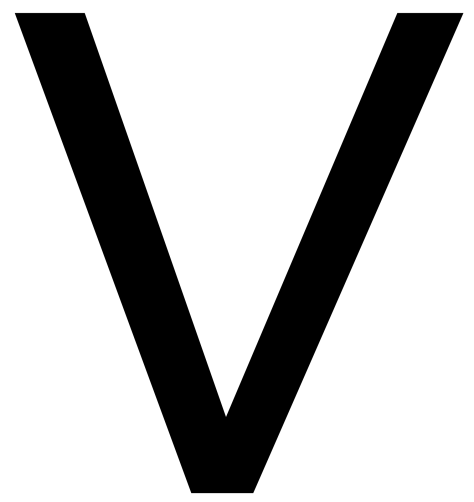

[iii]In Classical Latin, properly, ‘u,’ and ‘v’ are the same letter. Properly, a ‘V’ is nothing more than the capital form of the lowercase ‘u.’ Therefore, strictly speaking, the presence of a lowercase ‘v,’ in a classical Latin text, is an aberration. Oxford University Press wishes, eventually, to strike this aberration from all of its Latin publications, and I wish them well with this endeavour. Hence, the word ‘verbum,’ that one may observe in present O.U.P. Latin texts will eventually become ‘uerbum.’ However, this practice, today, is far from standard. I prefer this practice, and this is the practice that is employed by Peter V. Jones and Keith C. Sidwell’s Reading Latin: Text Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986. However, these texts—although I deem them more correct—are still in the minority. At present, in most Latin texts, a ‘u,’ or a ‘U,’ is employed to represent the letter ‘u,’ as a vowel; and a ‘v’ or a ‘V’ is employed to represent the letter ‘u,’ as a consonant. Hence, the letter ‘u,’ or ‘U,’ when short, can be said to represent the phonemes: /ʊ/ or /u/ and, when long it can be said to represent the phoneme /uː/. The letter ‘v’ or ‘V’ can be said to represent the phoneme /w/. This will be the practice employed in this present work. Although not our focus, in Church texts, the letter ‘v,’ or ‘V’ can be said to represent the phoneme /v/.

The technical name for the phoneme, /v/, is ‘voiced labiodental fricative.’

The Phonetics term, ‘voiced,’ informs us that vibrating air from the vocal chords is involved in the pronunciation of /v/.

The Phonetics term, ‘labiodental,’ informs us that both the lips and the teeth are involved in the pronunciation of /v/.

The English adjective, ‘labiodental’ is derived from the New Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘labiōdentālis, labiōdentāle,’ genitive singular: ‘labiōdentālis,’ genitive plural: ‘labiōdentālium,’ base: ‘labiōdentāl-.’ This New Latin word is derived from the Classical Latin 2nd-declension neuter noun, ‘labium,’ genitive singular: ‘labiī,’ which means ‘lip;’ and from the Classical Latin 3rd-declension masculine noun, ‘dēns,’ genitive singular: ‘dentis,’ genitive plural: ‘dentium,’ which means ‘tooth;’ and from the 3rd-declension adjectival suffix, ‘-ālis, -āle.’

Hence, etymologically, in this instance, the English adjective, ‘labiodental’ denotes ‘the use of the lips and the teeth in the articulation of a phoneme.’

The Phonetics term, ‘fricative,’ informs us that turbulence, caused by the air escaping from a narrow channel—in this instance, the mouth and lips—is involved in the pronunciation of /v/.

[iiii]As with ‘i,’ the Latin letter, ‘y,’ can function as a vowel or as a consonant. Its name in Latin is ‘ī Graeca’ which means ‘Greek “i.”’ When the character, ‘y,’ functions as a consonant, it is said to represent the phoneme, /j/, and on the occasions that ‘y’ functions as a vowel, when short it can be said to represent the phonemes: /ɪ/ or /i/ and when long—i.e. when a macron should appear above it, as: ‘ȳ’—it can be said to represent the phoneme: /iː/.