(Click the below link for a Microsoft Word version of this blog-post)

integer_multiplication_python

(Click the below link for a pdf version of this blog-post)

integer_multiplication_python

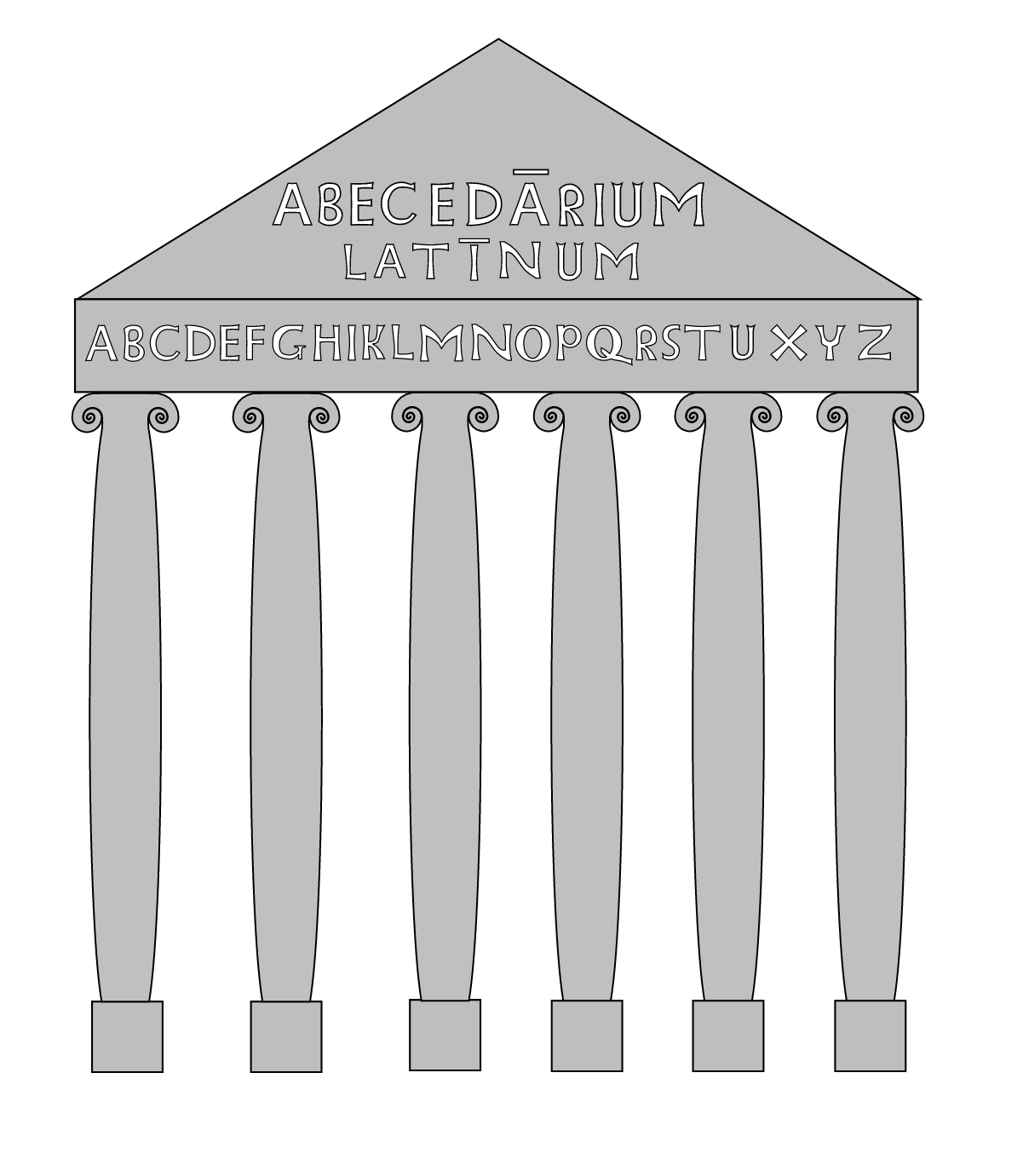

Figure 1: The Multiplication symbol. This symbol is used as a Multiplication Operator in Mathematics, but not as a Multiplication Operator in programming languages such as Python.

Figure 2: Instead of an ‘X’ symbol, we employ the asterisk symbol as a multiplication operator in Python. Press the keyboard key with this symbol depicted on it so as to effect multiplication.

Figure 3: What the asterisk symbol looks like rendered in Python’s default font.

What goes on, Arithmetically, in Multiplication?

In Arithmetic, Multiplication, is one of the four elementary operations. We ought to examine what occurs, arithmetically, in integer multiplication.

Let us take the equation:

2 × 4 = 8

. We pronounce the above equation, in English, as:

Two multiplied by four is equal to eight.

In the above equation, the integer, 2, is the multiplicand[1]. The integer, 2, is what is being multiplied by 4. I looked up the word ‘multiplication’ in a Latin dictionary[2], and its transliterated equivalent gave:

‘to make many,’

as a definition.

In the above equation, the:

×

symbol is termed ‘the multiplication operator.’ To restate: ‘operator’ is Latin for ‘worker.’ It is the multiplication operator that facilitates the ‘operation’ or ‘work’ of multiplication. In Python, we use the:

*

, or asterisk symbol, as a multiplication operator. In Python, the multiplication operator is known as a ‘binary operator[3]’ as it takes two operands. The operands, in question, are:

2

, the multiplicand, and:

4

, the multiplier.

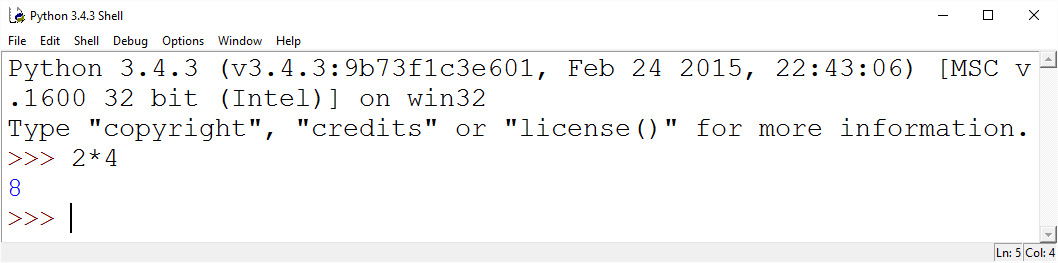

In the Python equation:

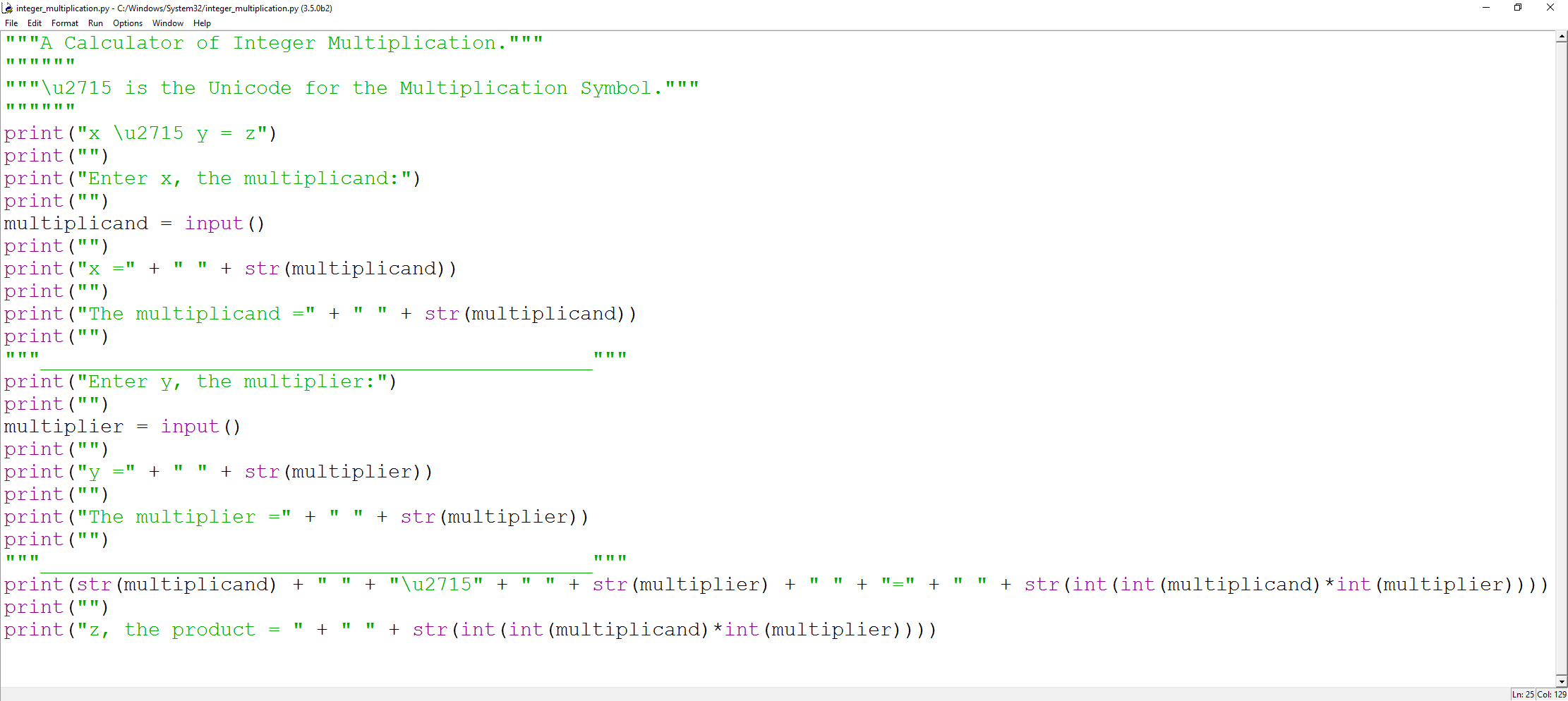

>>> 2 * 4

8.0

>>>

The multiplicand, 2, and the multiplier, 4, are the two operands that the binary operator:

*

takes.

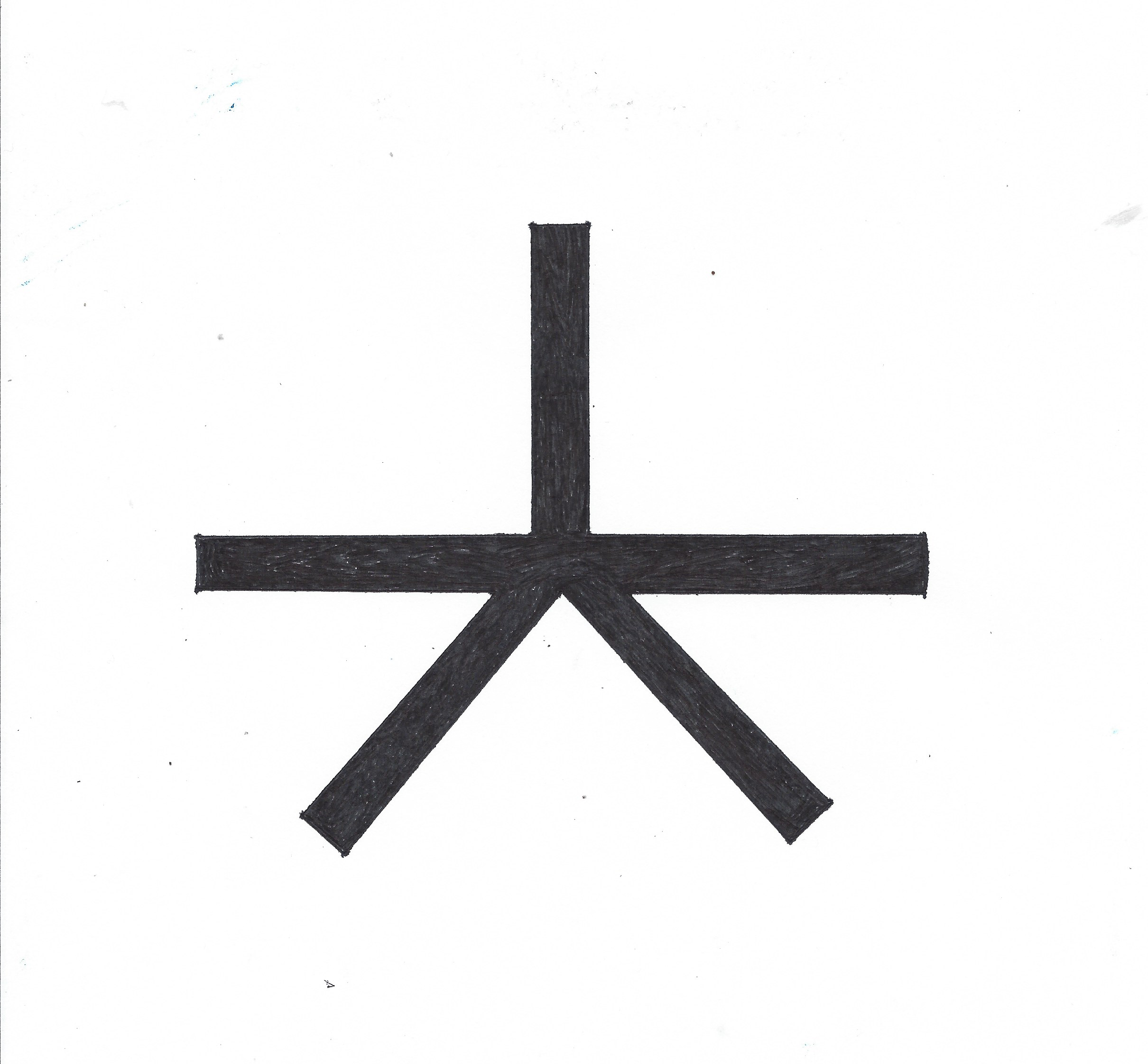

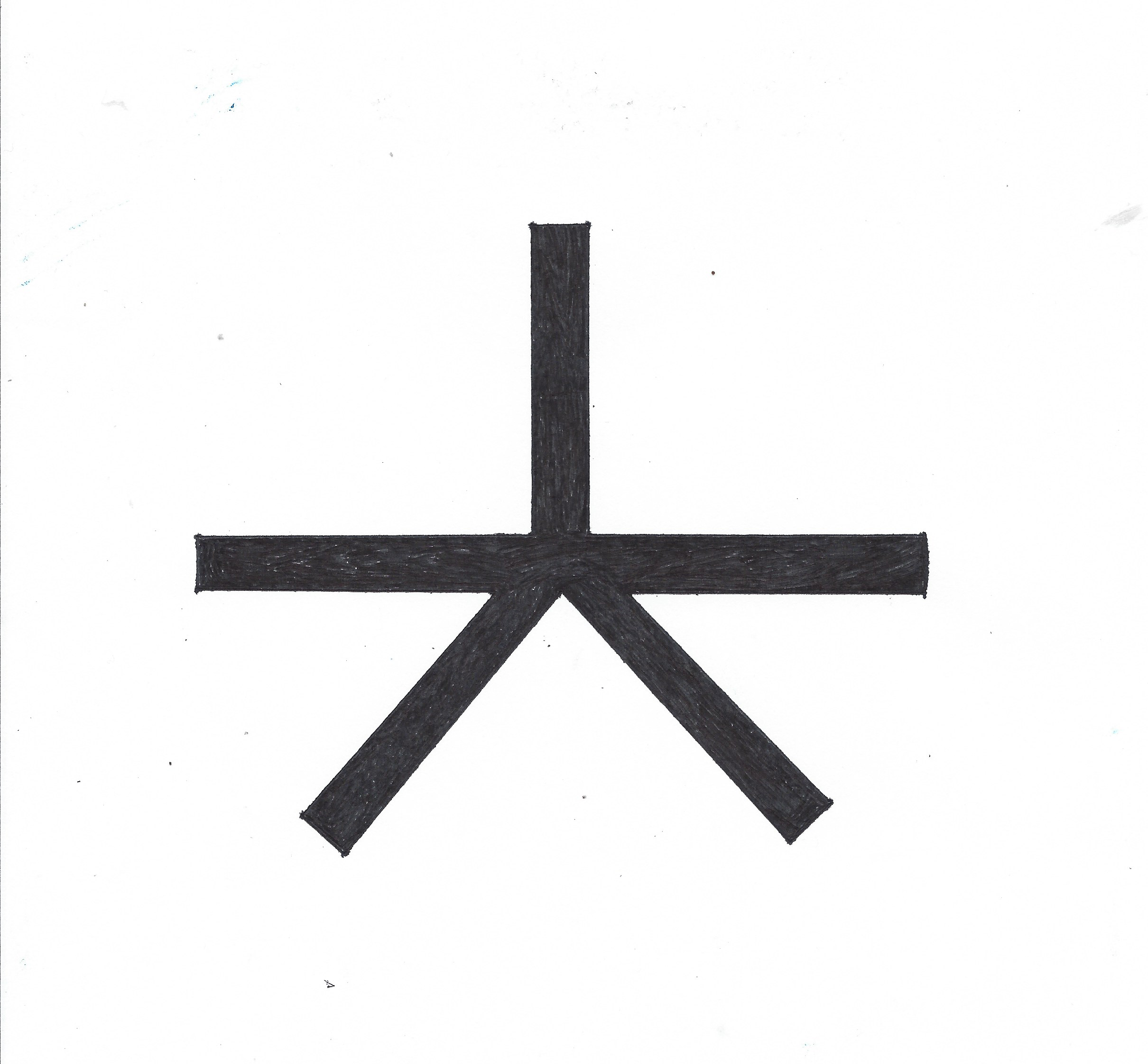

Figure 4: In Python, we use the * symbol as a multiplication operator. This is common to most programming languages. In the above example, we have multiplied 2 by 4, and have got the product, 8.

Let us return to the equation:

2 × 4 = 8

In the above equation,

4

is termed ‘the multiplier.’ In English, the ‘-er’ suffix denotes the agent, or doer of an action. It is the:

4

that is doing the dividing. 2 is being multiplied by 4.

In the equation:

2 × 4 = 8

the:

=

, or “equals sign,” is termed ‘the sign of equality.’ The sign of equality or equality operator tells us that 2 multiplied by 4 is equal to 8.

In the equation:

2 × 4 = 8

, 8 is termed ‘the product.’ The product is simply the result of multiplication.

The term, ‘product,’ comes from the Latin, ‘to lead forth.’[4]

The result of 2 being multiplied by 4 is 8, so, therefore, 8 is the product.

If we were doing ‘Sums’ in primary school, then:

8

, the product, would be our answer.

Integer Multiplication in Python

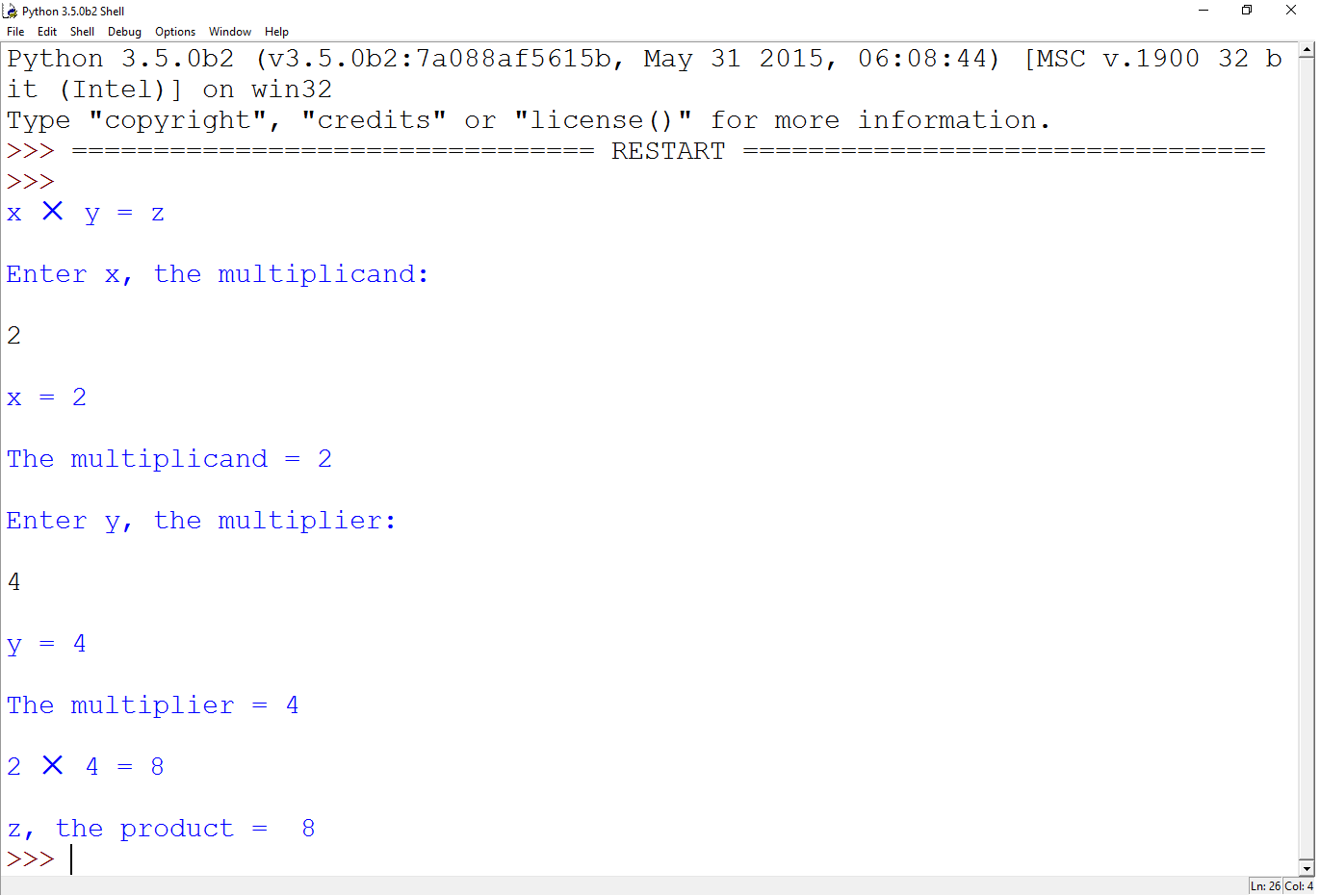

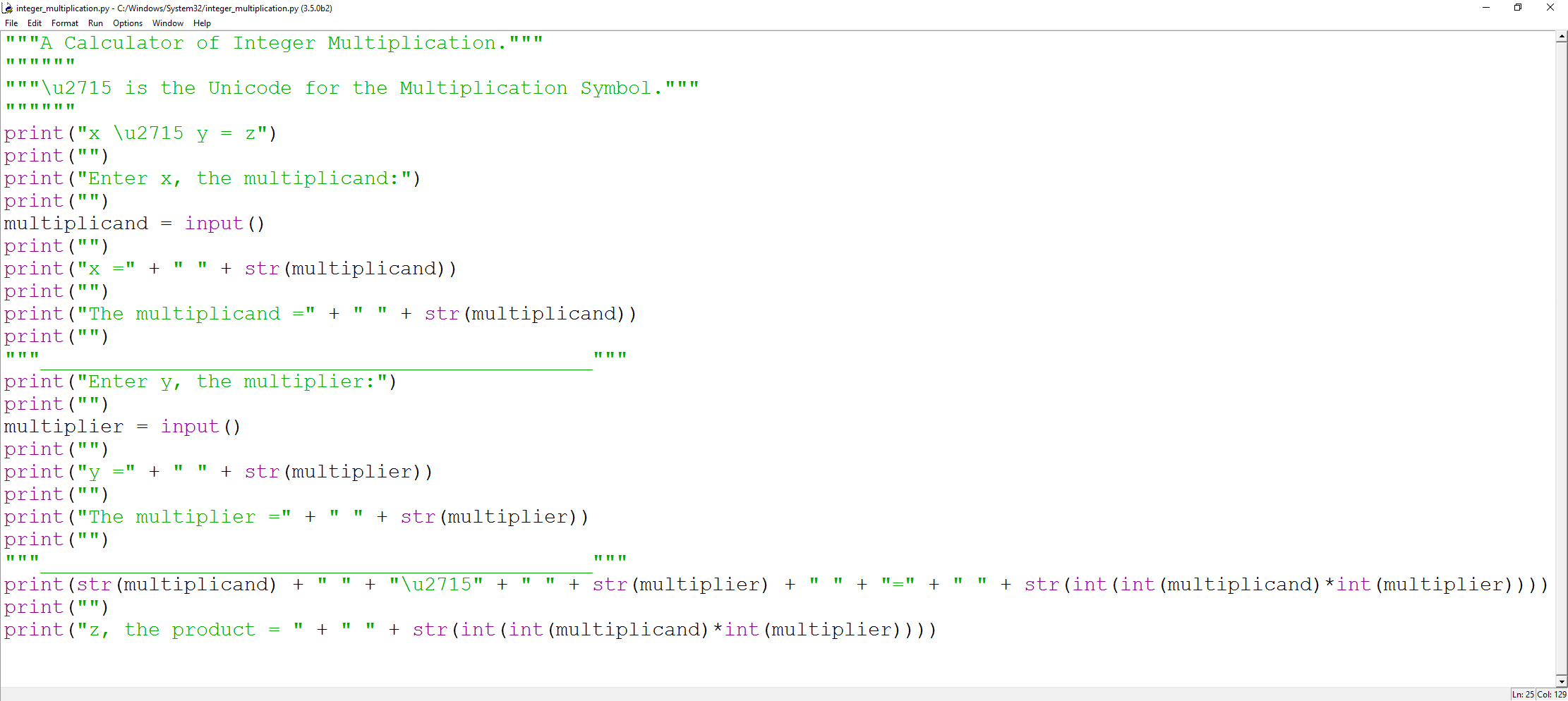

In this section, we shall program a simple Integer-Multiplication Calculator in Python.

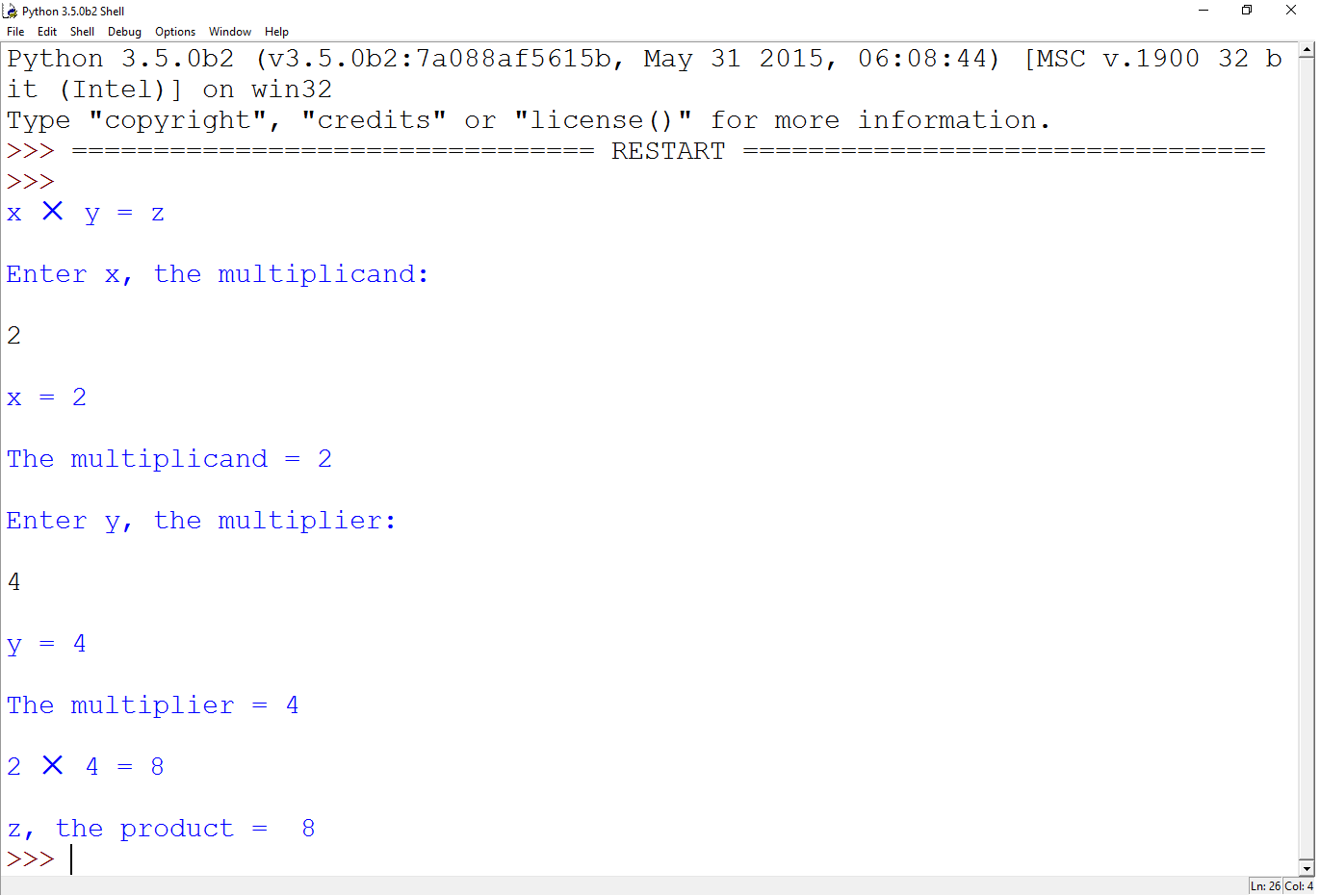

Figure 5: In the above-depicted program, we have programmed a simple Integer-Multiplication Calculator that requests the user to input a Multiplicand and a Multiplier, which are the two binary operands of the Multiplication Operator. The Integer-Multiplication Calculator then returns a product.

Figure 6: What the Integer-Multiplication Calculator, as depicted in Figure 5, outputs when we, the user, input the Multiplicand, 2, and the Multiplier, 4. As we can see, the program outputs the product, 8.

Glossary:

-er

- suffix

- denoting a person or thing that performs a specified action or activity: farmer | sprinkler

- denoting a person or thing that has a specified attribute or form: foreigner | two-wheeler.

- denoting a person concerned with a specified thing or subject: milliner | philosopher.

- denoting a person belonging to a specified place or group: city-dweller | New Yorker.

<ORIGIN> Old English -ere, of Germanic origin.

-ion

- suffix forming nouns denoting verbal action: communion.

- denoting an instance of this: a rebellion.

- denoting a resulting state or product: oblivion | opinion.

<ORIGIN> via French from Latin -ion-.

<USAGE> The suffix -ion is usually found preceded by s (-sion), t (-tion), or x (-xion).[5]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-iō, -ōnis’.

-ious

- suffix (forming adjectives) characterized by; full of: cautious | vivacious.

<ORIGIN> from French -ieux, from Latin -iosus.[6]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjectival suffix, ‘-iōsa, -iōsus, -iōsum.’

-ity

- suffix forming nouns denoting quality or condition: humility | probity.

- denoting an instance or degree of this: a profanity.

<ORIGIN> from French -ité, from Latin -itas, -itatis.

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension nominal suffix ‘-itās, itātis.’

equation

-

- [MATHEMATICS] a statement that the values of two mathematical expressions are equal (indicated by the sign =)

- [mass noun] the process of equating one thing with another: the equation of science with objectivity.

- (the equation) a situation in which several factors must be taken into account: money also came into the equation.

- [CHEMISTRY] a symbolic representation of the changes which occur in a chemical reaction, expressed in terms of the formulae of the molecules or other species involved.

<PHRASES>

- equation of the first (or second etc.) order [MATHEMATICS] an equation involving only the first derivative, second derivative, etc.

<ORIGIN> late Middle English: from Latin aequatio-(n-), from aequare ‘make equal’ (see EQUATE).[7]

<ETYMOLOGY> from the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective, ‘æqua, æquus, æquum,’ which means ‘equal;’ and the 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-tiō, (-tiōnis),’ which denotes a state of being. Therefore, etymologically, an ‘equation’ is ‘a state of being equal.’ Etymologically, therefore, an ‘equation’ is a mathematical statement that declares terms to be equal.

multiple

having or involving several parts, elements, or members: multiple occupancy | a multiple pile-up | a multiple birth.

- numerous and often varied: words with multiple meanings.

- (of a disease, injury, etc.) complex in its nature or effects; affecting several parts of the body: a multiple fracture of the femur.

- noun.

- a number that may be divided by another a certain number of times without a remainder: 15, 20, or any multiple of five.

- (also multiple shop or store)

BRITISH a shop with branches in many places, especially one selling a specific type of product.

<ORIGIN> mid 17th century: from French, from late Latin multiplus, alteration of Latin multiplex (see MULTIPLEX).[8]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘multiplex, multiplicis’ which means ‘manifold.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave.’

multiplex

-

- involving or consisting of many elements in a complex relationship: multiplex ties of work and friendship.

- involving simultaneous transmission of several messages along a single channel of communication.

- (of a cinema) having several separate screens within one building.

- verb. [with object] incorporate into multiplex signal or system.

<DERIVATIVES> multiplexer (also multiplexor) noun.

<ORIGIN> late Middle English in the mathematical sense ‘multiple’: from Latin.[9]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘multiplex, multiplicis’ which means ‘manifold.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave.’

multipliable

- adjective. able to be multiplied.[10]

multiplicable

- adjective. able to be multiplied

<ORIGIN> late 15th century: from Old French, from medieval Latin multiplicabilis, from Latin, from multiplex, multilplic- (see MULTIPLEX).

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘multiplicābilis, multiplicābile,’ which means ‘manifold.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave;’ and the Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘habilis, habile,’ which means ‘having.’ The Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘habilis, habile,’ is the adjectival form of the Latin 2nd-declension verb, ‘habeō, habēre, habuī, habitum,’ which means ‘to have.’ The etymological meaning of the term, ‘multipliable,’ therefore, is ‘having the ability to be multiplied;’ ‘having the ability to be made many;’ ‘having the ability to be made manifold.’

multiplicand

- noun. a quantity which is to be multiplied by another (the multiplier).

<ORIGIN> late 16th century: from medieval Latin multiplicandus ‘to be multiplied’, gerundive of Latin multiplicare (see multiply1).[11]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 1st-declension verb, ‘multiplicō, multiplicāre, multiplicāvī, multiplicātum,’ which means ‘to multiply, increase, augment.’ ‘Multiplicandum est’ is the neuter gerundive form. It means ‘that which must be multiplied;’ ‘that which must be made many.’

multiplication

- noun. [mass noun] the process or skill of multiplying.

- [MATHEMATICS] the process of combining matrices, vectors, or other quantities under specific rules to obtain their product.

<ORIGIN> late Middle English: from Old French, or from Latin: multiplication(n-), from multiplicare (see multiply1)[12]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension feminine noun, ‘multĭpĭcātĭo, multĭpĭcātĭōnis,’ which means ‘a making manifold,’ ‘increasing,’ ‘multiplying.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave;’ and the Latin 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-iō, -ōnis’, which signifies a noun denoting a verbal action. Therefore, the etymological definition of ‘multiplication’ is: ‘the action of multiplying;’ ‘the action of making many;’ ‘the action of making manifold;’ etc.

multiplication sign

- noun. the sign , used indicate that one quantity is to be multiplied by another, as in .[13]

multiplication table

- noun. a list of multiples of a particular number, typically from 1 to 12.[14]

multiplicative

- adjective. subject to or of the nature of multiplication: coronary risk factors are multiplicative.[15]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective, ‘multiplicātiva, multiplicātivus, multiplicātivum,’ which means ‘of multiplication;’ ‘of the action of making many;’ etc. From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave;’ and the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-īva, – īvus, -īvum’, which signifies ‘of,’ ‘concerning’. Therefore, the etymological definition of the English adjective, ‘multiplicative,’ is ‘concerning multiplication;’ ‘concerning the action of making many;’ ‘denoting multiplication;’ ‘denoting the action of making many;’ ‘of multiplication;’ ‘of the action of making many;’ etc.

multiplicity

- noun. (plural. multiplicities) a large number or variety: the demand for higher education depends on a multiplity of

<ORIGIN> late Middle English: from late Latin multiplicitas, from Latin multiplex (see MULTIPLEX).[16]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Late Latin 3rd-declension feminine noun, ‘multĭplĭcĭtas, multĭplĭcĭtātis,’ which means ‘multiplicity, manifoldness.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave;’ and the Latin 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-itās, itātis,’ which signifies a state of being. Therefore, the etymological meaning of the English term, multiplicity, is ‘the state of being many;’ ‘the condition of being many;’ etc.

multiplier

- noun.

- a quantity by which a given number (the multiplicand) is to be multiplied.

- [ECONOMICS] a factor by which an increment of income exceeds the resulting increment of saving or investment.

- a device for increasing by repetition the intensity of an electric current, force, etc. to a measurable level.[17]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the English verb ‘to multiply,’ which means ‘to make manifold,’ and the English nominal suffix ‘-er,’ which denotes the performer of an action. From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave;’ and the English suffix ‘-er,’ which denotes the performer of an action. Therefore, the etymological definition of ‘multiplier’ is ‘the number that multiplies.’

multiply1

- verb. (multiplies, multiplying, multiplied) [with object.]

- obtain from (a number) another which contains the first number a specified number of times: multiply fourteen by nineteen | [no object] we all know how to multiply by ten.

- increase or cause to increase greatly in number or quantity: [no object] ever since I became a landlord my troubles have multiplied tenfold | cigarette smoking combines with other factors to multiply the risks of atherosclerosis.

- [no object] (of an animal or other organism) increase in number by reproducing.

- [with object.] propagate (plants).

<ORIGIN> Middle English: from Old French multiplier, from Latin multiplicare.[18]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 1st-conjugation verb, ‘multiplicō, multiplicāre, multiplicāvī, multiplicātum,’ which means ‘to multipliy,’ ‘to increase,’ ‘to augment.’ From the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective, ‘multa, multus, multum,’ which means ‘many;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘plectō, plectere, plexī, plexum,’ which means ‘to plait,’ ‘to interweave.’ Therefore, the etymological definition of the English verb, ‘to multiply,’ is ‘to make manifold;’ ‘to make many;’ etc.

operator

- [MATHEMATICS] a symbol or function denoting an operation (e.g. ).[19]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the 3rd-declension masculine Latin noun, ‘ŏpĕrātor, ŏpĕrātōris,’ which means ‘operator,’ ‘worker.’ The Latin 3rd-declension noun, ‘opus, operis,’ which means ‘work,’ ‘labour.’ From the Latin 1st-conjugation verb, ‘operō, operāre, operāvī, operātor;’ and the 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-or, (-ōris)’ which denotes a performer of an action. Etymologically, as regards Mathematics, it is the operator that is said to perform the work of the operation.

operation

[mass noun] the action of functioning or the fact of being active or in effect: restrictions on the operation of market forces | the company’s first hotel is now in operation.

- [MATHEMATICS] a process in which a number, quantity, expression, etc., is altered or manipulated according to set formal rules, such as those of addition, multiplication, and differentiation.

<ORIGIN> late Middle English: via Old French from Latin operatio(n-), from the verb operari ‘expend labour on’ (see Operate)[20]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-declension feminine noun, ‘ŏpĕrātĭo, ŏpĕrātĭōnis,’ which means ‘a working,’ ‘a work,’ ‘a labour,’ ‘operation.’ From the Latin 1st-declension deponent verb ‘operor, operāre, operātus sum,’ which means ‘to work,’ ‘to labour,’ ‘to expend labour on;’ and the Latin 3rd-declension nominal suffix, ‘-iō, (-iōnis),’ which denotes a state of being. Etymologically, therefore, as regards Mathematics, an ‘operation’ is a ‘mathematical work;’ ‘mathematical working;’ a ‘mathematical labour.’ The mathematical work that would be carried out depends on the operator. For instance, if the operator be a plus sign, then the mathematical work to be carried out would be addition. Addition is a type of operation.

produce

- [GEOMETRY], DATED extend or continue (a line).

…

<ORIGIN> late Middle English (in sense 3 of the verb) from Latin producere, from pro- ‘forward’ + ducere ‘to lead’. Current noun senses date from the late 17th century.[21]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘prōdūcō, prōdūcere, prōdūxī, prōductum’ which means ‘to lead forth;’ ‘to bring forth;’ From the Latin preposition, ‘prō,’ which means ‘forth,’ ‘forward;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘dūcō, dūcere, dūxī, ductum,’ meaning ‘to lead.’ Therefore the etymological definition of the English verb, ‘to produce,’ is ‘to lead forth;’ ‘to bring forth;’ etc.

product

- [MATHEMATICS] a quantity obtained by multiplying quantities together, or from analogous algebraic operation.

<ORIGIN> late Middle English (as a mathematical term): from Latin productum ‘something produced’, neuter past participle (used as a noun) of producer ‘bring forth’ (see PRODUCE).[22]

<ETYMOLOGY> From the Latin participle ‘prōductum,’ which means ‘a leading forth;’ ‘a bringing forth;’ etc. From the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘prōdūcō, prōdūcere, prōdūxī, prōductum’ which means ‘to lead forth;’ ‘to bring forth;’ From the Latin preposition, ‘prō,’ which means ‘forth,’ ‘forward;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘dūcō, dūcere, dūxī, ductum,’ meaning ‘to lead.’ Therefore the etymological definition of the English verb, ‘to produce,’ is ‘to lead forth;’ ‘to bring forth;’ etc. Hence the etymological definition of the English noun, ‘product’ is ‘[the result that is] brought forth [from the operation of multiplication];’ etc.

[1] There seems to be some debate as to whether it be the first term – in this instance 2 – that is the multiplicand, or the second term – in this instance 4. However, the way that I worded it: “two multiplied by four” leaves us in no doubt that it is the first term – in this instance 2 – that is the multiplicand.

[2] multiplex icis, adj

[multus + PARC-], with many folds, much-winding: alvus…

Latin English Lexicon: Optimized for the Kindle, Thomas McCarthy, (Perilingua Language Tools: 2013) Version 2.1 Loc 62571.

Hence ‘multiplication,’ etymologically, means ‘to make manifold.’

See GLOSSARY

[3] See the chapter on UNARY AND BINARY OPERATORS

[4] The Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘prōdūcō, prōdūcere, prōdūxī, prōdūctum.’ From the Latin preposition, ‘prō,’ meaning ‘forth,’ ‘forward;’ and the Latin 3rd-conjugation verb, ‘dūcō, dūcere, dūxī, ductum,’ meaning ‘to lead.’ The etymological meaning of ‘product,’ therefore, seems to be: ‘[the result,] that which is lead forth [from the process of multiplication].’

[5] Oxford University Press. Oxford Dictionary of English (Electronic Edition). Oxford. 2010. Loc 362341.

[6] ibid. Loc 362542.

[7] ibid. Loc 234861

[8] ibid. Loc 461693.

[9] ibid. Loc 461727.

[10] ibid. Loc 461740.

[11] ibid. Loc 461758.

[12] ibid. Loc 461781.

[13] ibid. Loc 461787.

[14] ibid. Loc 461790.

[15] ibid. Loc 461792.

[16] ibid. Loc 461805.

[17] ibid. Loc 461810.

[18] ibid. Loc 461817.

[19] ibid. Loc 493860.

[20] ibid. Loc 493797.

[21] ibid. Loc 560683.

[22] ibid. Loc 560753.