I never got into the Star Wars franchise of films. I believe that the only Star Wars film that I have ever watched from start to finish was Phantom Menace. I know that Star Wars aficionados detest this film, but I remember really enjoying it.

Like most writers, I hope to, one day, complete a screenplay. I saw the Phantom Menace screenplay in a charity shop and bought it for dirt cheap.

Figure 1: The Phantom-Menace screenplay that I bought, a while back, in a charity shop.

I am teaching myself Classical Hebrew at the minute. The O’Reilly Dictionary asserts that Irish-Gaelic and Classical Hebrew are related languages. This would be a fascinating thing to research.

Figure 2: The O’Reilly Irish-English Lexicon from 1864.

A friend of mine has asked my help in writing a book that explores the linguistic and cultural similarities that existed between the Ancient Gaels and the Ancient Hebrews.

The way that I teach myself Classical Hebrew is by following a course on Youtube. In particular, I am following a course taught by Doctor Bill Barrick. Dr Barrick really gets into the nuts and bolts of Hebrew Grammar, which is what I like about his course in preference to many others.

Learning a dead language is difficult. Learning a dead language that has practically zero words in common with English – unlike Greek and Latin, say – is doubly difficult.

Classical Hebrew is a useful language to learn, even for purely secular purposes. As a Canaanite Language (1.) it is related to other Ancient Canaanite languges, such as Egyptian Hieroglyphics, and Classical Arabic, and Modern languages spoken in the Middle East, such as Modern Arabic.

For example, the Hebrew word for ‘head’ is ‘rōsh.’

The Aramaic (2.) word, the for ‘head’ is ‘rēsh.’

The Arabic word for ‘head’ is ‘ra’as.’

But learning a dead language, like Classical Hebrew, a language that one, especially in Ireland, is very unlikely to use, ever, in conversation, is extremely difficult. I remember when in Switzerland, on holiday, I was immersed in French and German. At night, prior to drifting off to sleep, I would hear the phonemes of French and German re-echo in my mind. A few months in such an immersion, and I would have become fluent. Such an immersion, although not totally impossible in Classical Hebrew (3)., is still not an easy task.

Modern Hebrew, from what I can gather, is a totally artificial construct. It was invented in the 1800s. They pronounce some phonemes in an Ashkenazic style, and other phonemes in a Sephardic style. Modern Hebrew uses an artificial compromised pronunciation. They have also, largely, abandoned the syntax of Ancient Hebrew. Modern Hebrew is essentially Hebrew words arranged in English syntax. English is very prepositional, so Modern Hebrew had to invent a load of prepositions, in the 1800s, that were never used, neither amongst the Ancient Hebrews, nor in Contemporary Jewish Ghettos. Certain Orthodox Jews find Modern Hebrew, for all the reasons listed above, blasphemous, and refuse to speak it.

So learning a dead language, such as Classical Hebrew, is a difficult task. One method that Doctor Bill Barrick has so as to overcome some of these difficulties, is to relate Ancient Hebrew words to modern-day entities.

I had been doing this myself, independently, with Ancient Greek.

I have a JVC cinema system, for example, and, thereupon, I fastened a sticker with the Ancient-Greek word:

κίνημα

or ‘kínēma,’ the Ancient-Greek word for ‘motion’ whence we derive the English word ‘cinema’ which describes ‘motion pictures.’

Doctor Bill Barrick would relate Ancient-Hebrew terms with the phenomena of modernity.

One phenomenon of Modernity to which he attached a Classical-Hebrew term just so happened to be Star Wars.

Figure 3: C3PO.

Doctor Bill Barrick theorised that the planet ‘Endor,’ the planet infested with Sasquatches known as ‘Ewoks,’ derived its name from the Ancient-Hebrew words, ‘Ayin’ and ‘Dor.’

Ayin Dor would translate to ‘Eye/Spring of Generation.’

The Ancient Hebrews used the term ‘eye’ so as to mean ‘natural water-spring.’ To the Ancient Hebrews, the earth, or ‘Ha-arets (4.) ‘ was a big eye, that would well up with water in places.

This is another benefit to learning languages. Not only does one learn the language itself, but one is also acquainted with the concepts of the culture that gave rise to that language.

Speaking of American Sci-Fi franchises, although I am a man, soon to be thirty, who is single, and who lives, for the most part, with his parents (5.) , I never got into Star Trek either.

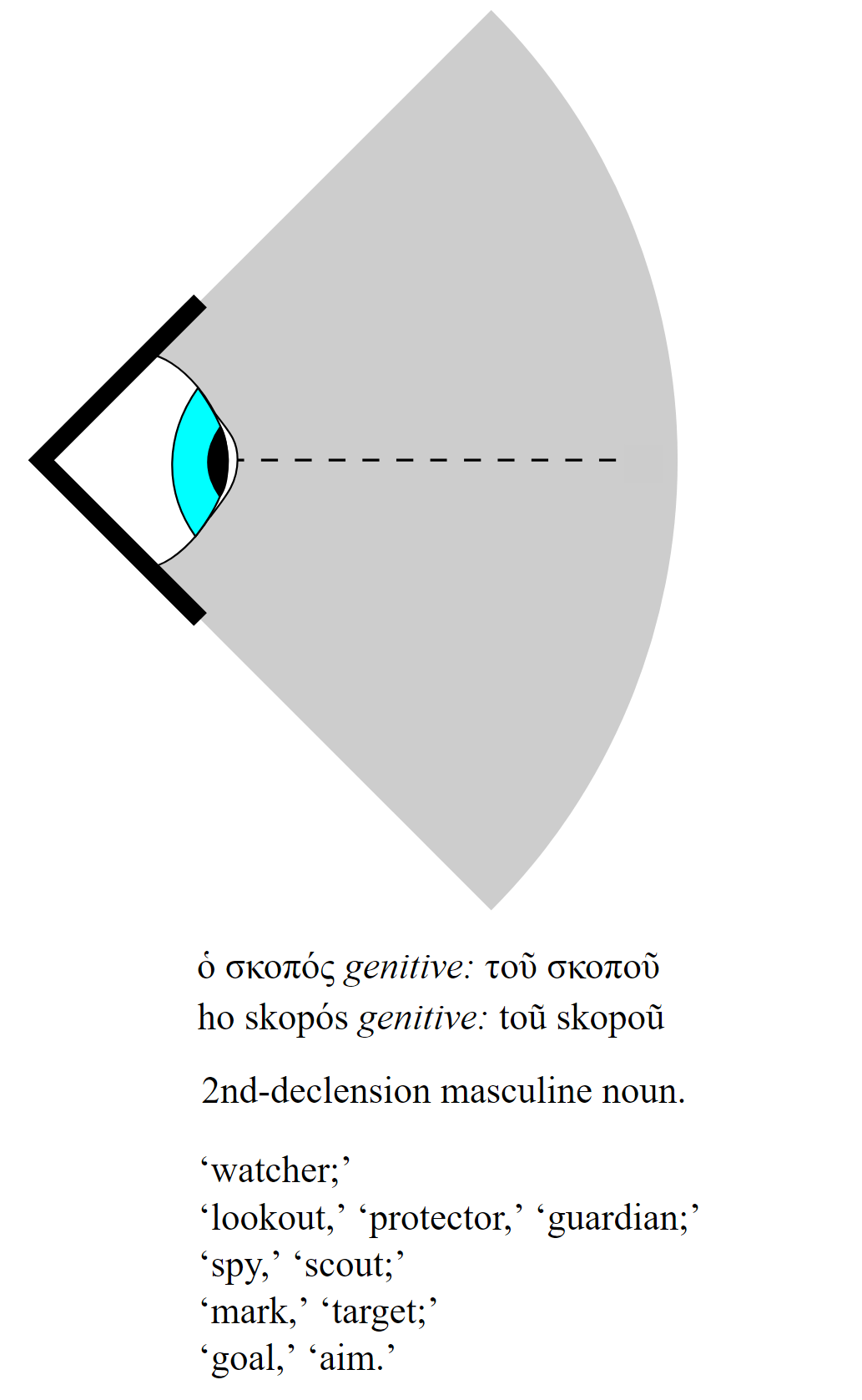

Recently, prior to passing away, Leonard Nimoy, the actor who played, Spok, said that the Trekker live-long-and-prosper hand symbol was based on the Hebrew character, shin.

Figure 4: Leonard Nimoy giving the live-long-and-prosper handsign.

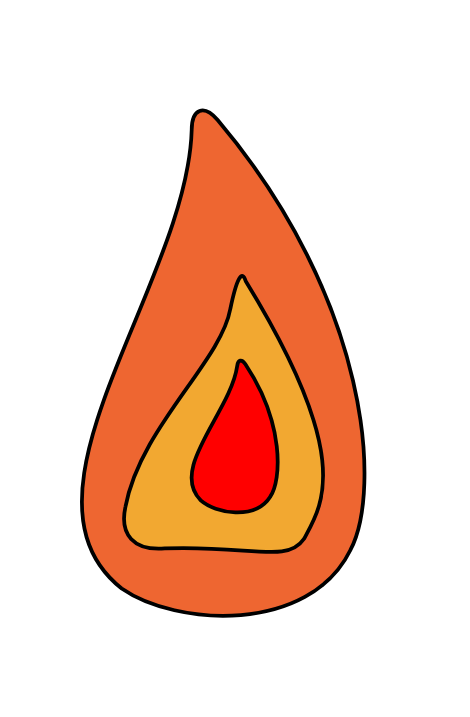

Figure 5: The 21st character of the Hebrew Alphabet, Shin. Shin means ‘teeth.’ The shin symbol represents that which devours, especially fire and romantic love.

Below are links to Word documents that contain the words, ‘Ayin’ and ‘Dor’, their spellings, and their meanings.

ayin_eyes_spring

dor_generation

(1.) Classical Hebrew’s linguistic classification.

(2.) The language of ancient Babylonia and Persia.

(3.) Modern-day Samaritans, for example, speak a form of Hebrew very close to Classical Hebrew, but I have no interest in packing my bags to go off to Samaria to see them.

(4.) ‘Erets’ in Hebrew means ‘land, country, earth, planet earth.’ It is ‘Haarets’ in its definite form. Hence the newspaper, Haaretz.

(5.) I am alluding to a quip made by Patrick Stewart in Ricky Gervaise’s sitcom, Extras.