Anatomy for Artists pdf

The above links to a pdf version of this blog post.

I hope, one day, in the dim and distant future, to become a great artist.

“LADY MACBETH:..To beguile the time, look like the time…”

In Act I Scene V of The Tragedy of Macbeth, Lady Macbeth tells Macbeth that so as to triumph in the present age, one must – at the very least – pretend to possess the sensibilities of the present age. To paraphrase another Shakespeare play:

“Deviousness, thy name is woman![1]”

Whereas Lady Macbeth said that to triumph over the age, we must imitate the age, it follows that to become great in a field, one must imitate the greats of that field.

So it goes with art. The Artists of the Renaissance tried to incorporate the Geometry of Euclid into their Art. Filippo Brunrlleschi (1377 – 1446) the architect who designed the dome of Florence Cathedral did this, and his contemporary, Leon Battista Alberti (1404 – 1472) wrote a book on this topic, De Pictura, which I am trying to read at the minute.

I, also, am reading up on Geometry, and attempting to find a way so as to incorporate it into my art.

Other Renaissance Artists, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, (1452 – 1592) were as much physicians as they were painters and sculptors. Leonardo Da Vinci had a diary – written in mirrored-coded script – in which he was ever recording anatomical observations.

My anatomical knowledge is extremely poor, but I am hoping to alter this fact.

I have bought a book, Human Anatomy: The Definitive Guide[2], and have begun to sketch copies of some of its illustrations.

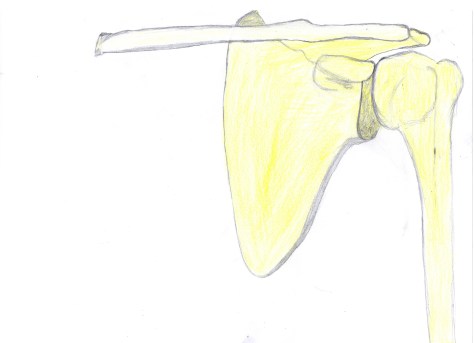

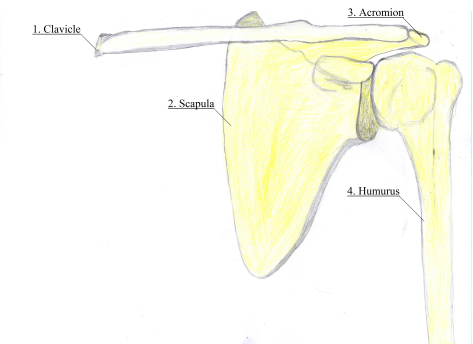

Figure 1: The Shoulder. I drew this with pencils.

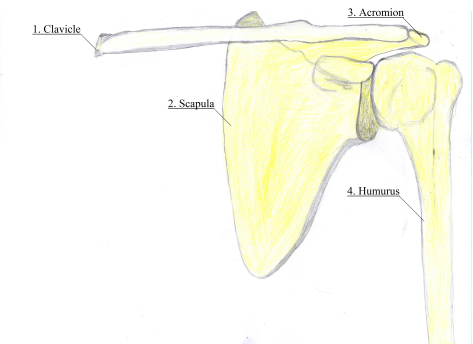

Figure 2: I used Microsoft Paint so as to label the various bones that I hand drew.

- Clavicle. The technical name for ‘Collarbone.’ It is the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally. The term ‘clavicle’ is derived from the Latin feminine noun, ‘clāvicula, clāviculæ,’ meaning ‘small key.’ Ultimately derived from the Latin feminine noun, ‘clāvis, clāvis,’ key.

- Scapula. The technical name for ‘Shoulder Blade.’ In medieval times, there existed an article of clothing called a ‘scapular,’[3] so called as it was a piece of cloth worn between the shoulder blades.

- Acromion. From the Ancient-Greek ‘ákros’ meaning ‘topmost,’ and the Ancient-Greek masculine noun ‘ho ȭmos,’ ‘the shoulder.’

“a bony projection from the outer end of the spine of the shoulder blade, to which the collarbone is attached”

[4]”

“noun. [ANATOMY] the bone of the upper arm or forelimb forming joints at the shoulder and the elbow.[5]”

As mentioned above, the humerus forms the elbow joint with the radius and the ulna. When this joint gets a bash, a funnily painful sensation results. Hence its name “the funny bone.” The similarity in spelling between ‘humerus’ and the adjective ‘humorous’ is to be noted. ‘Humerus’ and ‘humorous’ are largely homophonic[6]. ‘Humorous’ and ‘funny’ are synonyms, and I believe that this is why the joint formed by the humerus is called ‘the funny bone.’

[1] “HAMLET: Frailty, thy Name is Woman.” Hamlet: The Prince of Denmark Act I Scene II. William Shakespeare.

[2] DK. London. (2014).

[3] From the Latin 3rd-declension adjective, ‘scapulāris, scapulāre,’ which means ‘pertaining to the shoulder blade.’

[4] Encarta Dictionary.

[5] Oxford University Press. Oxford Dictionary of English (Electronic Edition). Oxford. 2010. Loc 336066.

[6] Adjective. Describing two – or more – words that are pronounced identically. From the Ancient-Greek adjective ‘homos,’ ‘the same,’ and the Ancient-Greek noun,’ ‘phōnḗ,’ which means ‘sound.’ The etymological sense of ‘homophonic’ is ‘words that have the same sound as one another.’