Click the below link for a pdf version of this article:

an_etymological_introduction_to_trigonometry

Click the below link for a Microsoft-Word version of this article:

an_etymological_introduction_to_trigonometry

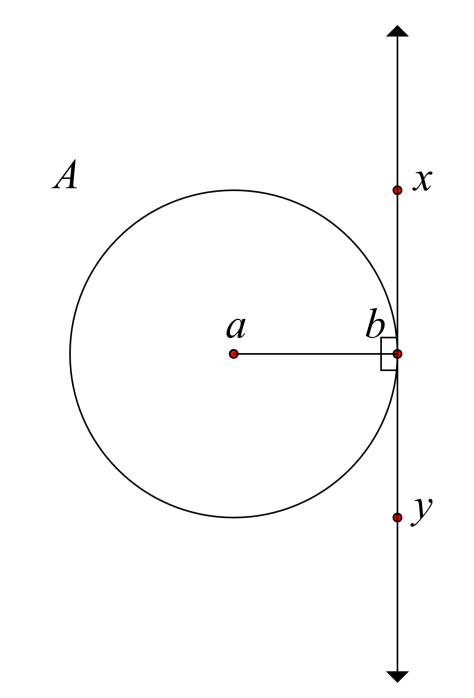

Figure 1: The mathematician, George Boole (1815-1864), was self-taught and fluent in Latin, Ancient-Greek, and Hebrew by the age of 12. I will be 30 in less than a month, and I am not even close to being fluent in any of these languages. However, I still cultivate an interest in these languages in some measure of poor imitation of the great man. It is certainly a great irony that subjects thousands of years old, such as Ancient-Greek and Latin, can make something so modern, such as Computer Programming, so much easier. If you have an interest in Science Fiction, you will notice that even in the far-flung future, scientists will name their bionic monsters after letters of the Ancient-Greek alphabet. The letter ‘Sigma,’ or Σ seems to be a favourite of Science-Fiction writers. In Ratchet and Clank: A Crack in Time, the Robot Junior Caretaker of the Great Clock is called Sigma 0426A.

Figure 2: Ecstasy tablets, very often, have the Ancient-Greek Majorscule, Sigma, stamped into them. So it is not only Computer Programming that a knowledge of Ancient-Greek will make easier: it will also give you a head start in Pharmacy!

Figure 2: Ecstasy tablets, very often, have the Ancient-Greek Majorscule, Sigma, stamped into them. So it is not only Computer Programming that a knowledge of Ancient-Greek will make easier: it will also give you a head start in Pharmacy!

I shall be studying QQI Level-V Videogame development in September. One of the modules of which this course comprises is called:

Mathematics for Programming

.

A huge part of this Maths module is Trigonometry. This is why I wish to develop an implicit knowledge of the fundamentals of Trigonometry, now, prior to beginning the module formally, in September.

The purpose of this article is to take a look at the etymological meaning of some of the key terms pertaining to Trigonometry.

‘Trigonometry’

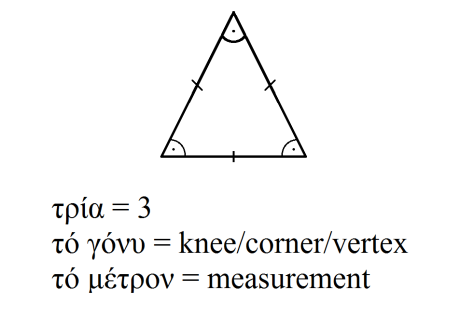

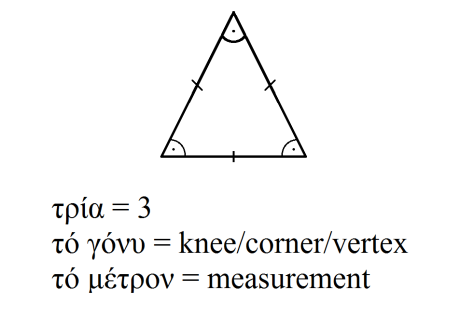

The term, ‘trigonometry’ is derived from four root words:

- ‘trí’ This is the Ancient-Greek Cardinal Numeral, 3.

- ‘tó gónu’ This is an Ancient-Greek third-declension neuter noun, which means ‘the knee;’ ‘the corner;’ ‘the vertex.’

- ‘tó métron.’ This is an Ancient-Greek second-declension neuter noun, which means ‘the measurement.’

- ‘-y.’ This is a noun-making suffix. It comes from the Latin substantive-adjective 2nd-declension neuter plural suffix ‘ [i]-a.’

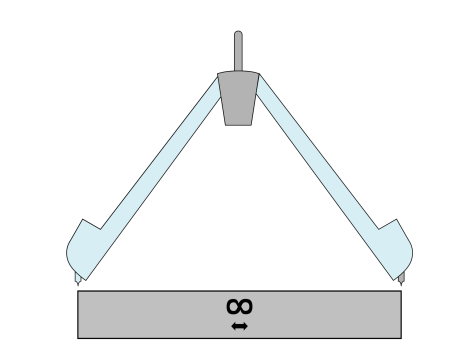

Figure 3: Etymologically, ‘Trigonometry’ is the study of the measurement of three-cornered polygons, or triangles.

The four root words, or etymons, listed above, when considered together, give us an etymological definition of ‘Trigonometry:’

The study of the measurement of three-cornered polygons.

The study of the measurement of polygons with three vertices.

The study of the measurement of triangles.

Now that we have the term ‘Trigonometry’ broken down, etymologically, let us now consider the Trigonometric term, ‘equilateral.’

‘Equilateral’

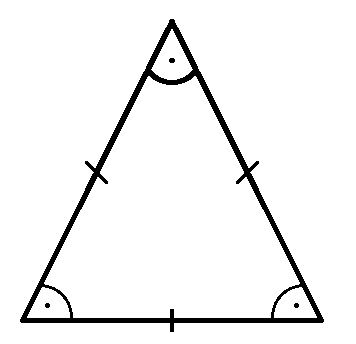

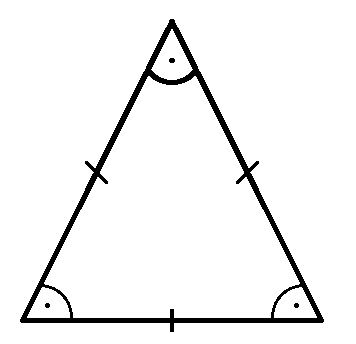

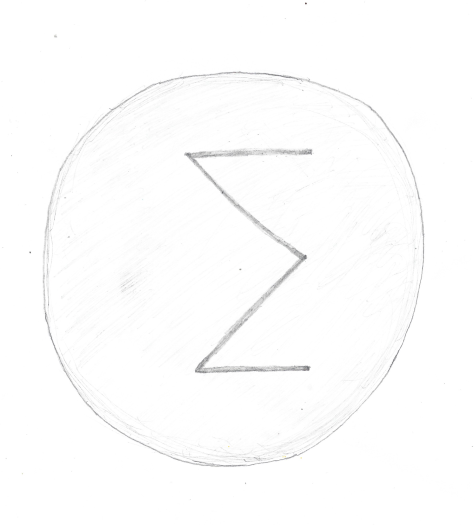

Figure 4: An equilateral triangle. An equilateral triangle has sides of equal length, and angles of equal magnitude. Each of an equilateral’s interior angles is equal to 60º in magnitude.

The term, ‘equilateral,’ can be broken down, etymologically, into three root words:

- ‘æqua, æquus, æquum.’ This is a 1st-and-2nd-declension Latin adjective that means ‘equal.’

- ‘latus, lateris.’ This is a 3rd-declension neuter Latin noun that means ‘side.’

- ‘-ālis, -āle.’ This is a 3rd-declension Latin adjectival suffix.

The three root words, or etymons, listed above, when considered together, give us an etymological definition of ‘equilateral:’

of [triangles] that possess equal sides[1]

Now that we have the term ‘equilateral’ broken down, etymologically, let us now consider the Trigonometric term, ‘isosceles.’

‘Isosceles’

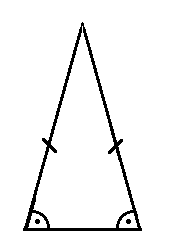

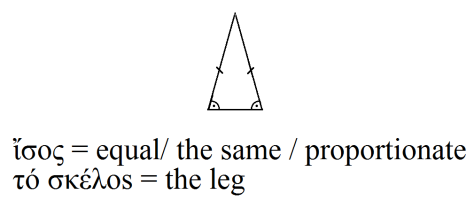

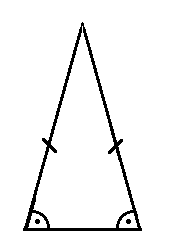

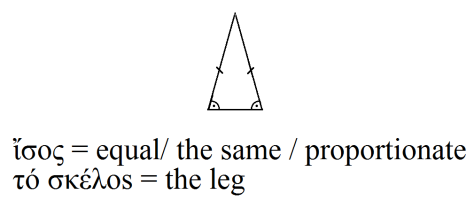

Figure 5: An isosceles triangle. An isosceles triangle has 2 sides equal in length, and two angles equal in magnitude.

Figure 6: An isosceles triangle has two ‘legs’ or sides equal in length.

The term, ‘isosceles,’ can be broken down, etymologically, into two root words:

- ísos. This is an Ancient-Greek adjective that means ‘equal,’ ‘the same,’ ‘proportionate.’

- tό skéllos. This is an Ancient-Greek third-declension neuter noun that means ‘leg.’

It is funny how, in Ancient-Greek, the sides of triangles are called ‘legs’ and the corners of triangles are called ‘knees!’

The two root words, or etymons, listed above, when considered together, give us an etymological definition of ‘isosceles:’

A triangle [that possesses two sides] that are equal in length.

A triangle [that possesses two sides] that are the same in measurement.

A triangle [that possesses two sides] that are proportionate.

Now that we have the term ‘isosceles’ broken down, etymologically, let us now consider the Trigonometric term, ‘scalene.’

‘Scalene.’

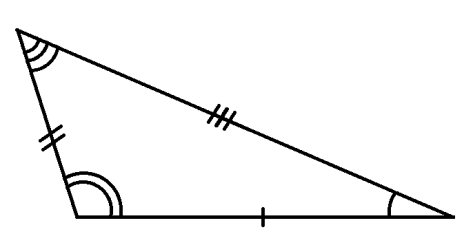

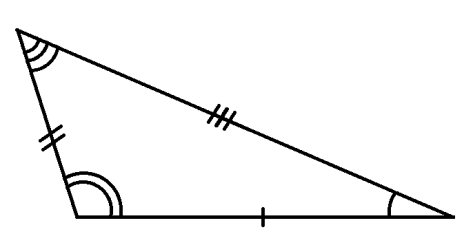

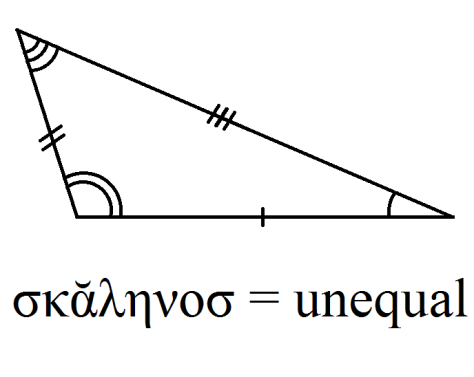

Figure 7: A Scalene Triangle. As we can see from the above diagram, a scalene triangle is one which possesses 3 sides, all of unequal length; and 3 interior angles, all of unequal magnitude.

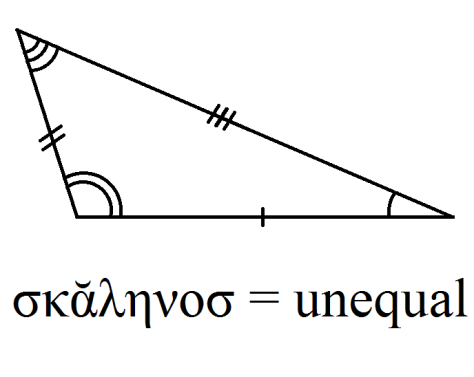

Figure 8: The Trigonometric term, ‘scalene’ is derived from the Ancient-Greek adjective, ‘skălēnos,’ which means ‘unequal.’

The term, ‘scalene,’ can be broken down, etymologically, into the root word:

- ‘skălēnḗ, skălēnos, skălēnón’ This is a 1st-and-2nd-declension Ancient-Greek adjective that means: ‘uneven,’ ‘unequal.’

When we consider the root word, or etymon, listed above, then we can come to the following etymological definition of ‘scalene:’

[of a triangle whose sides are] of unequal [length.][2]

[1] Et sequitur: equal angles. It follows, according to mathematical logic, that if a triangle’s sides be all equal in length that its interior angles will, likewise, be all equal in magnitude.

[2] Et Sequitur: and whose interior angles are unequal in magnitude. It follows, according to mathematical logic, that if a triangle’s sides be all unequal in length that its interior angles will, likewise, be all unequal in magnitude.

Figure 2: Ecstasy tablets, very often, have the Ancient-Greek Majorscule, Sigma, stamped into them. So it is not only Computer Programming that a knowledge of Ancient-Greek will make easier: it will also give you a head start in Pharmacy!

Figure 2: Ecstasy tablets, very often, have the Ancient-Greek Majorscule, Sigma, stamped into them. So it is not only Computer Programming that a knowledge of Ancient-Greek will make easier: it will also give you a head start in Pharmacy!