mathsandcomedy.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/gnosis_falsely_so_called.pdf

Gnosis Falsely So Called:

Introduction:

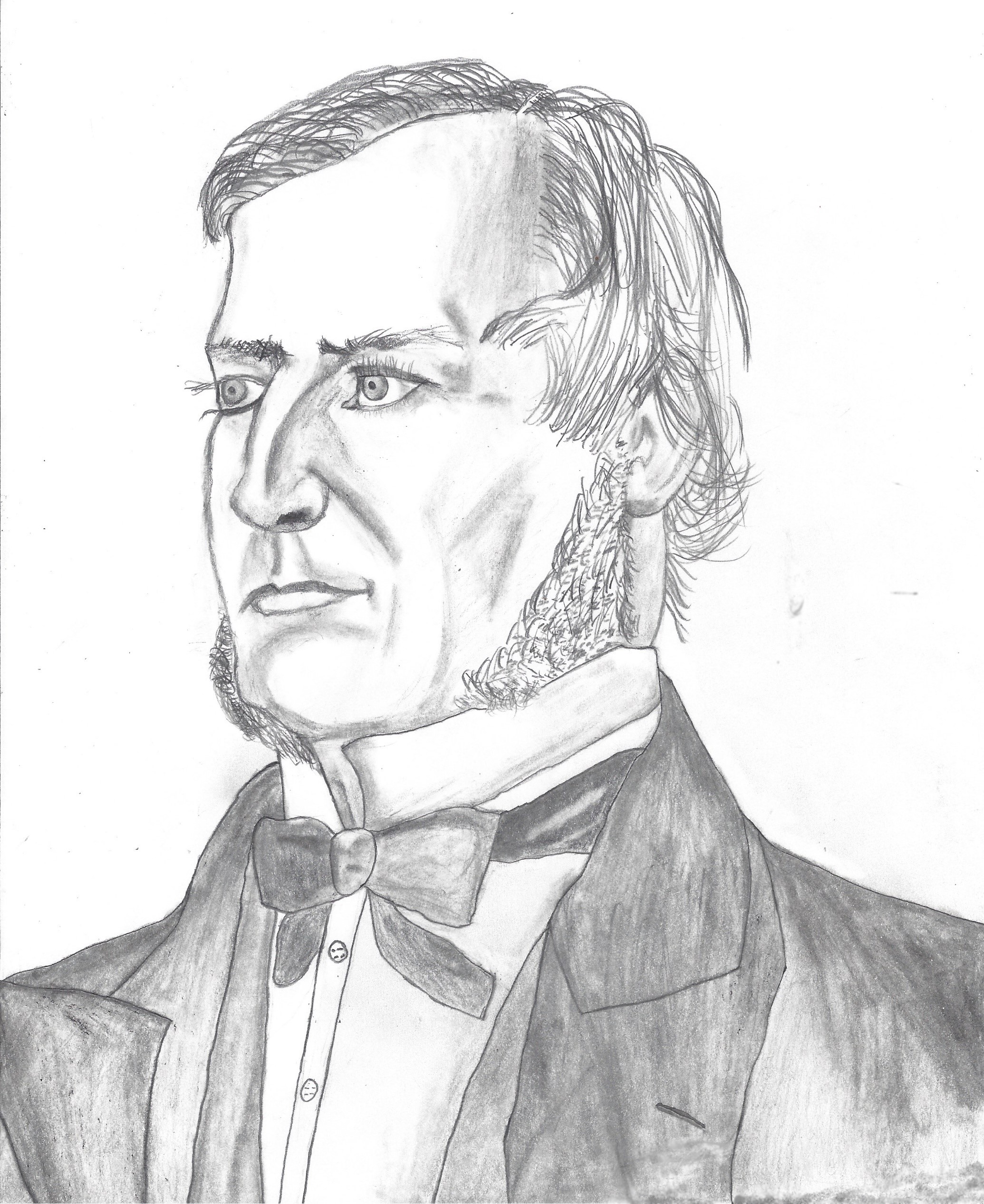

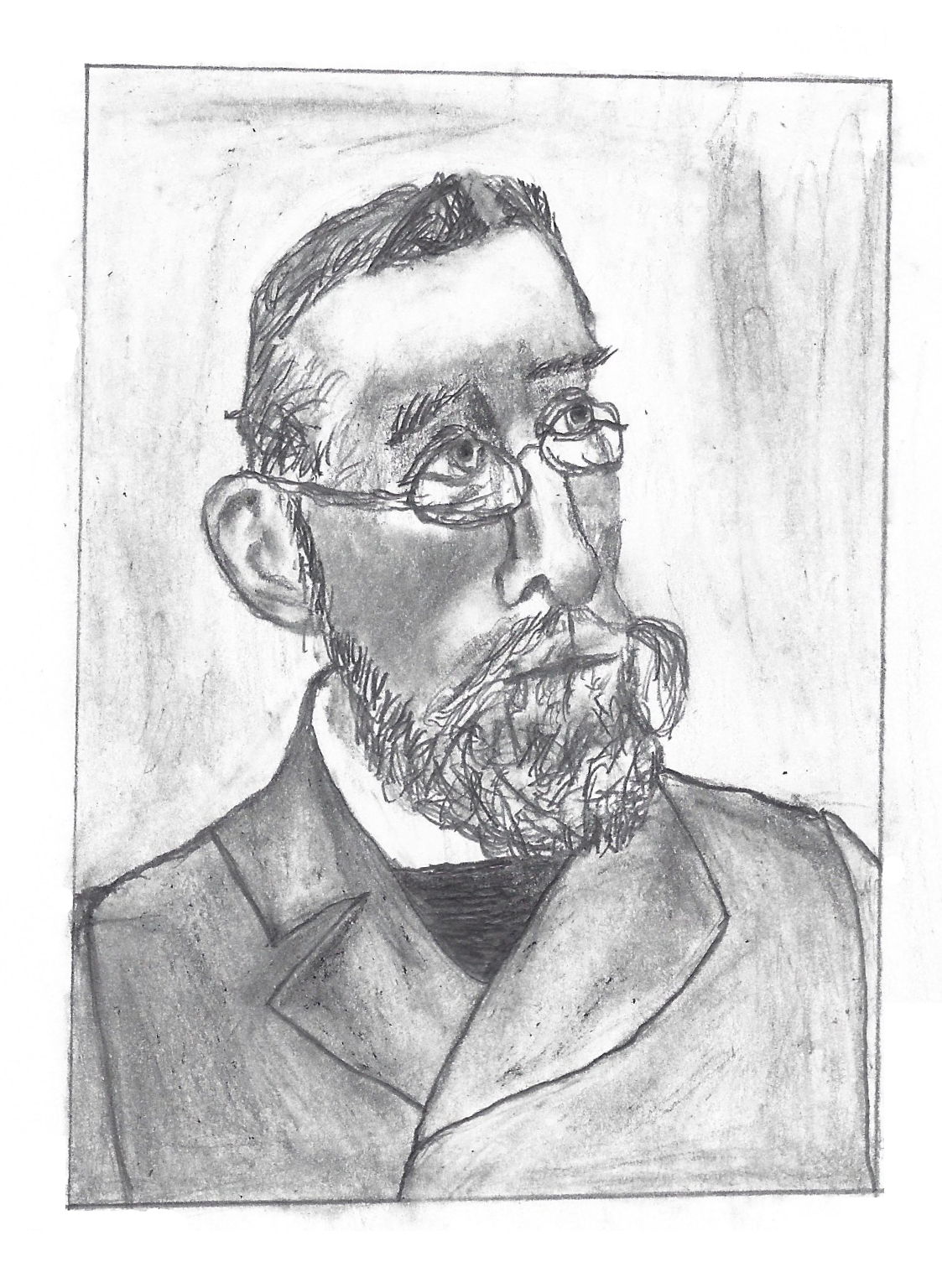

I could listen to Dr. Robert McNair Price (1954-) all day. The MythVision YouTube channel, seems to be where this great sage hangs out, these days. I can listen to 30-minute talk after 30-minute talk of his for ages.

The poor man seems failed, though, and not long for this world. Saturn mows down all living things beneath his scythe to make way for a newer, fitter, generation, and, alas, Price will one day—like us all—be harvested by the Grim Reaper, Saturn. I hope and pray, though, that he might live for another decade or more.

At present I am reading his Jesus is Dead (2007), which is a critical examination of arguments made by Christian apologists in favour of the alleged resurrection of Jesus Christ. What I love about this book, is that Price ridicules and mocks the apologists’ rogues gallery when such scorn be necessary. In this article, I shall examine what Price said concerning 1st Timothy 6:20 in a recent MythVision video.

Body:

The Independent Fundamentalist Anabaptist, Matt Powell, recently came out with a YouTube “movie” promoting creationism entitled: Science Falsely So Called (2018).

This film derives its title from the King James Version: Blayney Edition (1769) rendering of 1st Timothy 6:20:

‘O Timothy, keep that which is committed to thy trust, avoiding profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of science falsely so called:’

.

Let us examine 1st Timothy 6:20 as it appears in the Clementine Vulgate:

‘Ō Tīmothee, dēpositum cū̆stōdī, dēvītāns profānās vōcum novitātēs, et oppositiōnēs falsī nōminis scientiae,’

‘ÓÓ Tiimóthee, deepósitum cuustóódii/custóódii, deevíítaans profáánaas vóócum novitáátees, ét oppositióónees fálsii nóóminis sciéntiææ,’

‘ÓÓ Tiimóthee, deepósitum custóódii, deevíítaans profáánaas vóócum novitáátees, ét oppositióónees fálsii nóóminis sciéntiææ,’

. My translation of the Clementine Vulgate is as follows:

‘O Timothy! Keep that which was placed down, avoiding the novelties of profane voices, and [the] oppositions of science falsely so named.’

Note how similar my translation of the Vulgate is to the KJV’s translation. In the KJV:

‘… the oppositions of science falsely so called.’

is basically a transliteration of the Vulgate’s:

‘…oppositiōnēs falsī nōminis scientiae.’

Thus, the KJV is not the literary bastion of anti-catholicism that the likes of the New-Independent-Fundamentalist-Anabaptist Pastor, Steven Anderson, would like you to think that it was. The Catholic Vulgate was a major influence on the KJV translators.

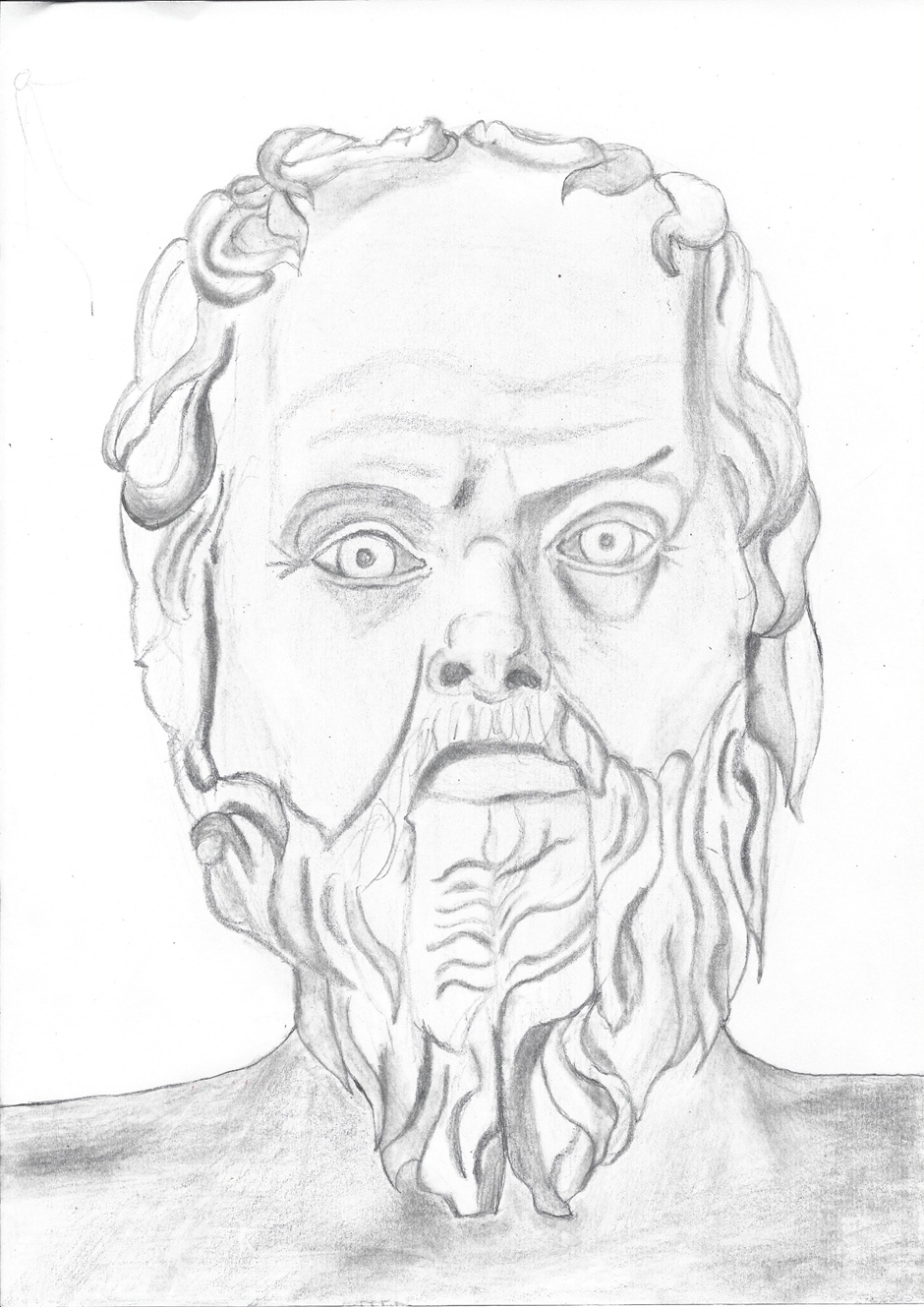

According to Price, the verse delineated suprā is a nod and a wink, by the author of 1st Timothy, to the Antitheses of Marcion of Pontus (circā 85 C.E.- circā 160 C.E.)

Marcionism, in a nutshell, was the rejection of the Old Testament, and its God, as evil.

Marcion wrote a book, in which he contrasted the Old-Testament God with the New-Testament God, and this—now lost—book was entitled: Antitheses.

Let us now examine 1st Timothy 6:20 in the Koine Greek of Scrivener’s (1894) Textus Receptus:

Ὦ Τῑμόθεε, τὴν παρακαταθήκην φύλαξον, ἐκτρεπόμενος τὰς βεβήλους κενοφωνίας καὶ ἀντιθέσεις τῆς ψευδωνύμου γνώσεως·

‘Ō̂ Tīmót͡hee, tē̂n parakatat͡hḗkēn phúlaxon, ektrepómenos tā̀s bebḗlous kenop͡hōníās kaì antit͡héseis tē̂s p͡seudōnúmou gnṓseōs.’

Let us examine the Greek verse, suprā, in Young’s Literal Translation (1862) of the Textus Receptus:

‘O Timotheus, the thing entrusted guard thou, avoiding the profane vain-words and opposition of the falsely-named knowledge,’

.

According to Dr. Bob, the Greek verse, suprā, is a warning by Saint Paul, against Marcion’s book: The Antitheses and against the gnosticism of the Marcionite sect. According to the author of 1st Timothy, the Marcionite sect has a false Gnosis, whereas the more orthodox Pauline sect, represented in the Book of 1st Timothy, has the true Gnosis; the true salvific knowledge.

Summary:

Doctor Robert McNair Price’s scholarly ouevre is fascinating. Price’s humorous demeanour, in both his speeches and his writings, rivets the hearer/reader to material that is at times difficult. We are discussing the turgid fields of Ancient History and Textual Criticism, after all. In Jesus is Dead (2007) Price argues that the Bible becomes much more interesting, and much more fun to study, once one jettisons the notion that this Bible constitutes an inerrant revelation from a God… and I strongly agree with him concerning this point.

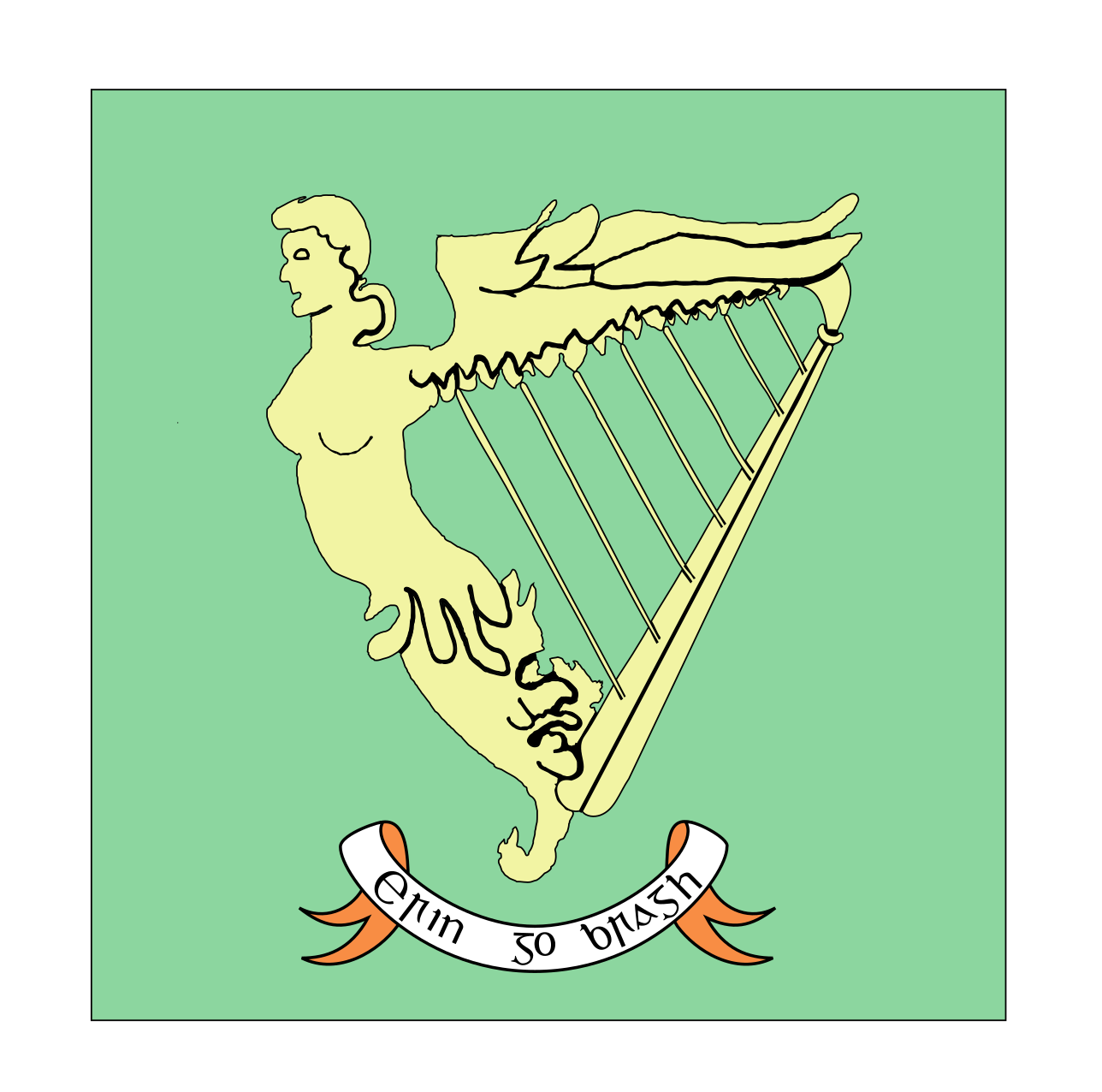

Figure 2: I drew this 1916 Rising flag in Inkscape. The motto, ‘Erin go Bragh,’ means: ‘Ireland till [the Last] Judgement;’ ‘Ireland forever.’

Figure 2: I drew this 1916 Rising flag in Inkscape. The motto, ‘Erin go Bragh,’ means: ‘Ireland till [the Last] Judgement;’ ‘Ireland forever.’